Join BirdNote tomorrow, November 30th!

Illustrator David Sibley and actor H. Jon Benjamin will face off in the bird illustration battle of the century during BirdNote's Year-end Celebration and Auction!

Migration happens once every year. And then again maybe six months later.

Depending on several factors, at most times of the year, there are many birds on the move. Some are merely altitudinal migrants, descending when the weather turns fowl in the mountains. The large majority undertake a twice-yearly journey that can span continents and oceans. Raptors harness thermals to carry them, songbirds power through with the help of highways of wind, and seabirds soar on the oceanic air streams. Two major reasons birds are on the move are to avoid harsh weather and, perhaps more importantly, to take advantage of seasonal or episodic food sources that good weather brings. There are migratory birds in every place on earth and the reasons, methods, and extremities are as diverse as the species that practice.

This phenomenon is inherently mystical and fascinating, and piques the human curiosity. After all, with the rare modern exceptions of hunter-gatherers who follow seasonal food sources, people don’t migrate. For millennia, our ancestors in the Northern Hemisphere observed that when green sprouts began to push through the ground, they started seeing swallows again. And by the time the harvests began, the fields had grown quiet once more.

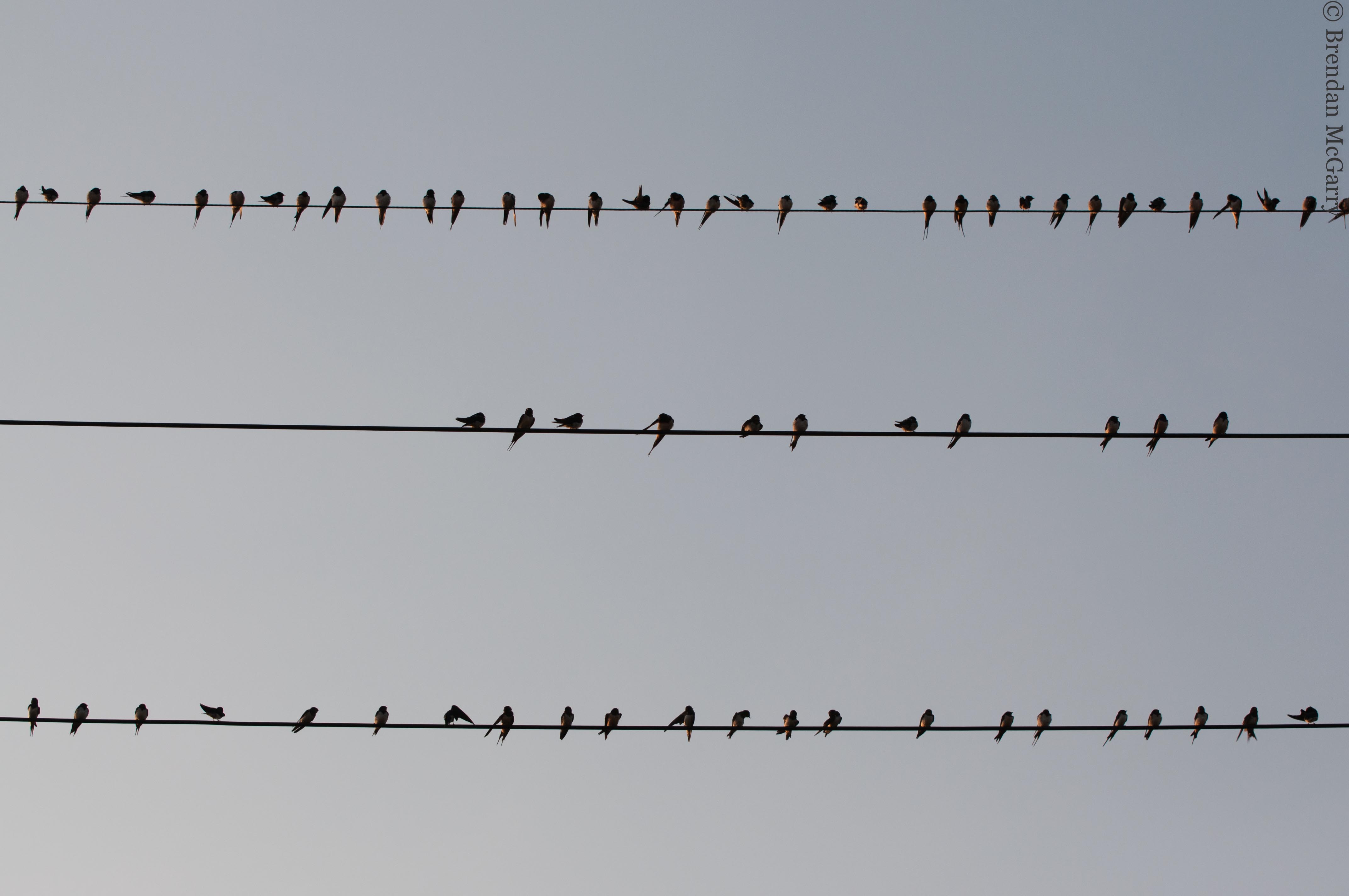

With the onset of spring in the Northern Hemisphere, things are starting to ramp up. I for one have started to notice the signs. The ancient Greeks believed that absent swallows had burrowed underground. Thankfully, I know that the ones I've started to see again this year have just been in Mexico and beyond.

These migratory journeys often defy our concepts of reality. Discussions about the record-holding long-distant migrants have shifted from the Arctic Tern (flying from the Arctic Circle to Antarctica), to the Bar-tailed Godwit (flying from Alaska to New Zealand), to the Sooty Shearwater (Northern Hemisphere to Southern), and back again. The Bar-tailed Godwit is held to be the longest nonstop migrant, some flying about 7,000 miles in one go, without any dilly-dallying (they fly over water and cannot float!). Sooty Shearwaters and Arctic Terns have both been recorded in distances exceeding 30,000 miles. In 2006, Sooty Shearwaters broke the record for the longest-distance animal migration at around 40,000 miles, making a figure-8 tour around the North and South Pacific each migration. 2010 research results on Arctic Terns showed them traveling in excess of 40,000 miles in their year of travel. (All this knowledge is a result of bird-banding and lightweight radio-tags.) Seabirds certainly make some of the most spectacular hauls, and they spend a lot of time preparing for the trip, adding around 50 percent of their body weight to store fat reserves.

Many of the songbirds that breed in the United States - or even as far north as Alaska or Canada or the Arctic - spend winter in the tropics. Their trip is equally astounding. Imagine: a tiny bird that nested in your backyard may spend the winter in central or South America. And they make most of their journey at night! To support habit for these birds in their wintering area, consider buying shade-grown coffee.

It may seem odd that diurnal, typically terrestrial species are flying high in the sky at night. But their predators, who normally would be challenging to avoid, are asleep. Also, although birds fuel up before they leave, refueling is required, which they cannot do at night. Finally, the most interesting part is that some are using the stars to navigate! We long pondered how many birds were migrating at night until a technique using an instrument called an Emlen Funnel was invented in 1966. (This is an entire article in itself. If you're curious, read more at The Journal of Experimental Biology.)

Go out on a still night during peak songbird migration, and you may hear the calls of migrating songbirds. In the city, even above the noise of urban life, they may be audible. Residing in the suburbs or away from busy roadways, one may hear hundreds, even thousands, of individual birds representing dozens of species. (Yes, it takes a bit of practice.) Some enthusiasts actually set up their own recording devices and use programs to sort and count what birds fly over at night. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology embarked on research doing exactly this, but on a larger scale along the Eastern Seaboard, allowing for studies both on reasons for nocturnal flight calls and on population dynamics.

While these birds are on the move, they face many threats, not the least of which is the human influence. Our massive buildings and lights confuse birds in nightly migration. New York City’s lights kill an estimated 10,000 birds a year. We've erased habitat at both ends of their journeys and also disturbed their stopover points along the way. In short, these amazing travelers have not only the sheer obstacles of the elements, predators, and distance to come up against, but humans as well. Research allows us to understand this phenomenon, and it also helps us evaluate how we can alter our ways to benefit birds.

Birds migrate in such mass that they can even be noticed migrating in other ways. Meteorologist and Pacific Northwest weather expert, Cliff Mass, posted a blog entry a couple years ago with fantastic Doppler radar images, showing birds moving over the Puget Sound area at night during autumn. They are moving south and there are a lot of them!

Migration is something we still don’t fully understand, and this article is just the tip of the iceberg on this fascinating subject. If you are interested in learning more, I’d recommend Scott Weidensaul’s popular account, Living On the Wind: Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds. We are lucky to have some amazing technologies – from sound recordings and radar imaging to lightweight radio-tags – to help us understand an otherworldly behavior. Next time you look at a warbler in your back yard, imagine it flying to Costa Rica. I'll bet you'll appreciate it that much more.